Super apps in Europe are the dream of the zealots of the « Network Effect ». One app for the users to do everything in line with payments and to lock them inside a prison. A prison where they could be fed only with what you authorised to be fed. Convenience Nightmare, it’s ultimate proof. It makes investors drool, ready to sign a check, and product teams geek out to create the best stack.

But this dream crashes into reality. A super app will never have a global footprint. They are, by design, answers to specific lacks of infrastructure in a given region. The vision of a super app for Europe is not just a lazy idea but also bound to fail.

Europe has tried centralised digital experiences before. Take Minitel in France in the 1980s, an early version of bundled services, long before the internet. State backed it, so it worked. Minitel ran on monopolistic telecom rails and lived inside a nationally scoped ecosystem. But those conditions are gone. In today’s liberalised, multi-country, privacy-conscious Europe, there’s no soil for a private player to build such a vertically integrated walled garden.

How many shanzhai (a Chinese word for bad copy) of Alipay / WeChat Pay have I seen among Europeans? But Alipay and WeChatPay were created to fill an obvious lack of infrastructure for paying.

China’s Payment Void: The Real Reason Super Apps Took Off

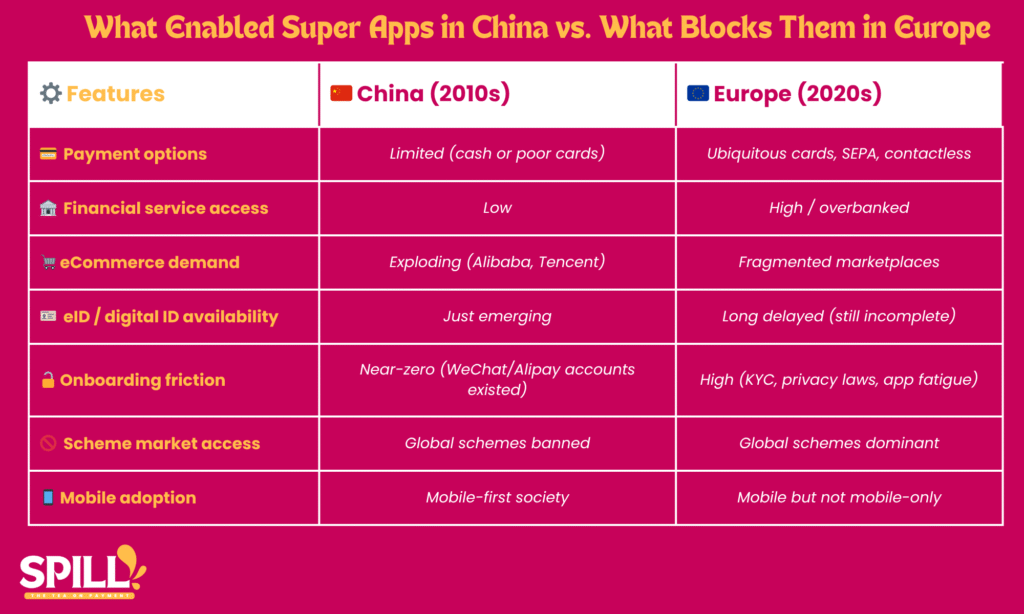

In China, before Alipay and WeChat arrived in early 2010, strong limits existed on paying.

People could use Cash with the biggest facial amount for a note being 100 yuan (which barely today can pay for 3 McDonald’s menus) or bank cards that did not allow e-commerce, which was booming (Alibaba is a marketplace giant, Tencent is an online entertainment giant).

Local smartphone brands (Xiaomi, Oppo, Vivo, Huawei, …) flooded the market with cheaper devices than Korean or American ones.

Banks were unable to give a solution for retail banking that was convenient, cheap to use and safe. Mainland China barred access to the Global schemes.

Therefore, this absence allows the existence of emerging local technologies that would tackle all the hurdles, without the assistance of a foreign company. PayPal failed miserably to enter the market because of stringent restrictions on customers’ data access.

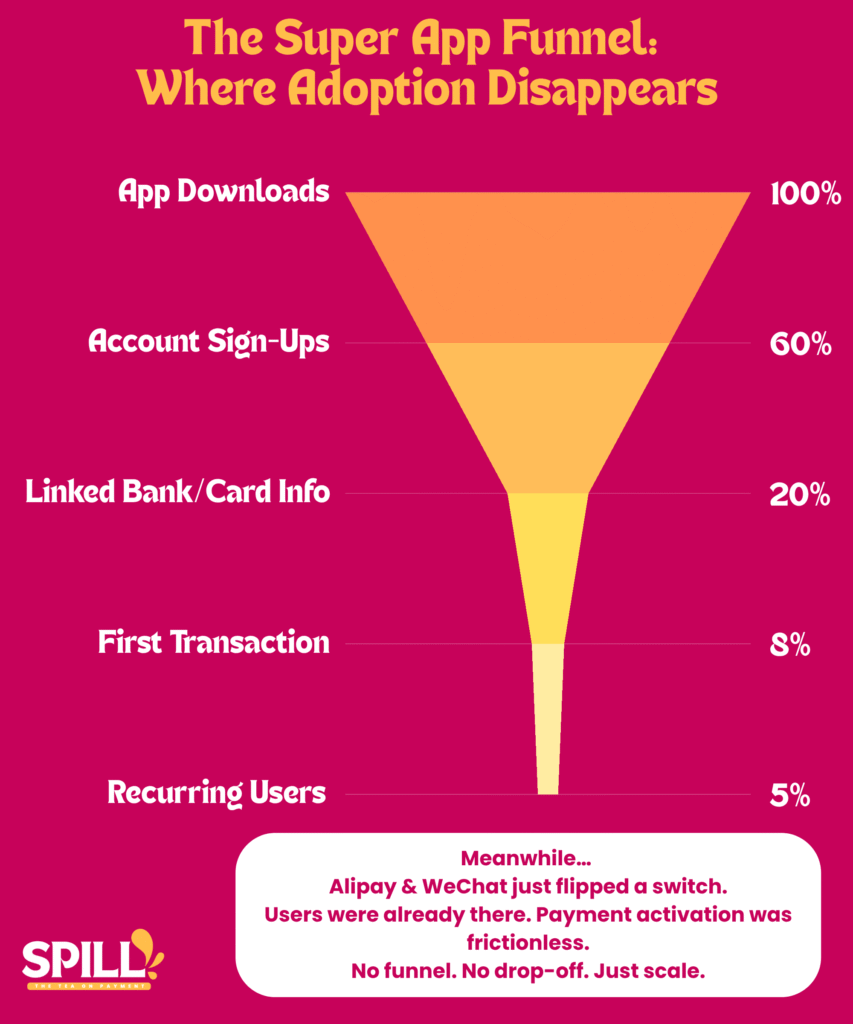

Now you have the full picture, you probably get why those two platforms became infrastructures themselves. People could pay, have access to some basic financial services, but both companies also embedded services that they already offered. Their businesses initially were not financial services. Tencent offered a social network/messaging app, and Alipay was created to offer an easy one-click payment solution to check out on the marketplaces of Alibaba (Alibaba or Tmall)

If we zoom out from China, Grab Pay was created for the same reason in Southeast Asia. Grab Pay wanted to simplify the payment experience for both riders and hailers, constrained by multiple issues, such as the absence of proper identification, expensive card payment, etc.

Super Apps in Europe: Built for a Context That Doesn’t Exist

In Europe, we don’t lack infrastructure; it is even the contrary, we have got layers and layers of infrastructure. People are overbanked, cards are widespread, easy to use, across all channels. No problems of accessing financing or financial services other than payments. But those layers of infrastructure create a problem of interoperability, not a problem of access for users.

In Europe, we have an app for each service, and people love it. If an app centralises too many services, it is suspicious. In Europe, Convenience has some limits, and one of the biggest is privacy concerns.

And more importantly, putting multiple services under one roof doesn’t automatically create an ecosystem. What many so-called European “super apps” attempt is simple aggregation. They offer food delivery, a wallet, a marketplace, and a ride service, but that’s not genuine integration. There’s no shared identity, no network logic, no daily embeddedness. They remain feature portfolios, not operating systems for daily life like WeChat has become in China.

Europeans are deeply privacy-conscious, and culturally, they value it: a strict limit between private and public life. Even in the most southern countries, people have their little secrets. Banks are reliable institutions, but no one will think about giving them more than what they have. A siloed approach is typical of Western countries.

Beyond the privacy concern, Super Apps also face a problem of localisation. European markets are not as unified as they seem to be. Regulations are similar, but regulations do not make everything. Cultural practices are different, and languages are different. There is no common language like in India, China, Brazil, Latin America or North America. We all live in our own way, even if we share the same rules.

If Tencent and Alibaba Gave Up, Why Are We Still Trying?

Even the super app specialists (Tencent, Alibaba) did not dare to enter the Common market. They had the licenses, they had the compliance structure, they had the money.

But they also had this insight: Europe is too fragmented, too complex, and too sensitive to localisation missteps. When payments are involved, trust is not transferable. A bad translation or UX pattern can kill adoption.

That’s why they both focused on serving Chinese living overseas and tourists. Even though that was a challenging job. In 2016, Alipay announced its first partnership with a European entity, Banque Edel, a small French retail bank belonging to E-Leclerc Cooperative. Nobody understood what Super App was about, reason Alipay had to sign with a way smaller bank than a « real acquirer ».

At that time end of 2017, I did a training for EBA for their Winter School 2017 to explain what Alipay is. My banker friends were suspicious of what was at stake.

If the original super apps didn’t try to replicate themselves in Europe, maybe it’s not because they failed. No, they finally understood the model doesn’t travel.

Some Analysts forecast a 25% CAGR for super apps in Europe. Fine. But forecasts are an illusion, because they don’t frame what is a super app, plus they don’t account for:

- The cost of running payment infrastructure across borders. Borders can still be painful in Europe. Unified regulation still has loopholes, PSD III is working on resolving some of them.

- The slow rollout of digital ID has been in the pipeline for more than a decade 2014.

- The gap between what users say they want and what they adopt.

- The second gap is between onboarding and transactability. How many users can choose to onboard and never become recurring users?

Let’s Stop Importing Fantasies and Start Building for Europe

Cards were supposed to be universal, too. My conversation with Goran in my podcast painted a different reality. Many people still don’t have proper cards (potentially only a cash card). It is not because they’re unaware, but because of the cost to have a whole infrastructure up and running. It is not made for free; users as well as merchants pay for this heavy infrastructure.

Now, super apps are next? Maybe in pitch decks. Not on the ground.

Europe’s path forward is at the image of the European Union as a political entity. The difficult choice to make is between more federal integration and keeping the status quo. We are at a crossroads. Same for payment. Fragmentation shows obvious limits:

- Monopolistic practices from the bigger

- Low level of operability and therefore blocking any ambitious plan to transition from legacy systems to new infrastructure, more in phase with the 21st century

- Emergence of non-European alternatives that could threaten our sovereignty, like USD stablecoins.

At this stage, Europe needs more horizontal cooperation:

- Digital public infrastructure (like eID and open wallets).

- Standards that promote interoperability (like PEPS, EPI, and SEPA).

- Modular, composable services that work across borders.

Trying to build a WeChat for Europe is like trying to sell central heating in Singapore. It misses the context. The dream of a European super app isn’t just unlikely. It’s misguided.

Let’s stop importing fantasies. Let’s build for reality.